History and Information About Skulls

Day of the Dead Festival (Dia de los Muertos) is a Mexican festival both celebrating and remembering the dead. From mid-October through the first week of November, markets and shops all over Mexico sell special art and foods honoring the dead, most in the form of skulls and skeletons. Mexicans have no qualms about death, instead viewing it as a natural progression of life. November 1 is to honor and remember dead infants and children (angelitos) and November 2 is set aside to remember dead adults.

Day of the Dead Festival (Dia de los Muertos) is a Mexican festival both celebrating and remembering the dead. From mid-October through the first week of November, markets and shops all over Mexico sell special art and foods honoring the dead, most in the form of skulls and skeletons. Mexicans have no qualms about death, instead viewing it as a natural progression of life. November 1 is to honor and remember dead infants and children (angelitos) and November 2 is set aside to remember dead adults.

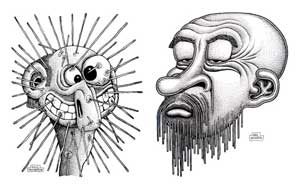

Mexico’s most prolific lithographer, Posada made popular an art form that was almost lost in his time. His favorite theme was skeletons doing everyday human activities. He did this to bring to the viewer’s attention the message that death is inevitable for everyone. His most famous image is “Catrina” also called “Stylish Lady”, “Bony Lady”, or simply “Death”. Here he was making fun of the common women of the day who imitated the upper class by wearing their cast-off clothing. Again his message was clear: we are all the same under the skin. The famous skull logo of The Grateful Dead was from his work.

While most of us think all skeletons look alike, scientists can tell the age, sex, race, general health, time of death, and usually how a person died by examining his skeleton. Many cultures and religions of yesterday and today think skulls have magical powers.

Amongst the Irian Jaya tribe of Indonesia, the skull of one’s ancestor is revered and cared for. The body is left to decompose until the skull can be easily removed. The eldest male child then receives the skull and cares for it, using it as a pillow at night, and carrying it by day, so that it will always be protected.

The Skull Actually Consists Of 28 Bones. The Only One That Moves Is The Mandible Or Lower Jaw.

Hoaxes or ancient objects of power? The origins of the Crystal Skulls are unknown, and though some have been debunked as recently created hoaxes, others reveal that they were created by a technology that we do not have access to today. Those who have worked with the skulls claim that they receive information in the form of visions and flashes of insight, and many believe the skulls to have healing power.

The skull is so important to the Babanki people of the Camaroon grasslands that representations of the head decorate almost al utilitarian items. They revere the ancestral spirits embodied in the skulls of deceased ancestors. These are kept by the eldest male of a lineage. When a family relocates, they must first build a dwelling to house the skulls. If they cannot preserve an ancestor’s skull, they perform a ritual in which libations are poured upon the ground and then utilize dirt from that location to represent the skull of the deceased.

We have all seen pictures of shrunken heads – or maybe seen those rubber replicas. But did you ever ask yourself why anyone would bother to shrink a head in the first place? The Jivaro people of the Andes feud a lot between their tribes. But if they manage to kill the enemy, they must perform an elaborate ritual to purify yourself of the killing. Durning this time, the warrior is temporarily ostracized from the tribe and a skeleton is painted on his body. In a process which takes several days, he removes the skull (through the neck) and shrinks the enemy’s head, creating a “Tsantsa” which traps the spirit of the enemy inside the head, where it cannot haunt him.

The Starchild Project claims that a weirdly shaped child’s skull found in a cave in Mexico proves the existence of human-alien breeding. The brain case of the skull is 200 cc larger than a normal human’s. For thousands of years, the head has been a symbolic of the mind, spirituality and Oneness. In his “L’Ascension de l’humanite” (Paris 1958) Herbert Kuhn suggests that the decaptitation of corpses during prehistoric times marked Man’s discovery of the spiritual principle residing in the head, as opposed to the vital principle which resided in the body as a whole.